Celebrating Atypical Minds, adhd-community: philosophium: Do I have any...

Do I have any followers with ADHD? Or does anyone have some really good information on it? I want to write a character who has ADHD but I don’t know anything about it except the basics so I’m looking to educate myself. Any help beyond a wiki article would appreciated!

Friends, what would you like to see in an ADHD character?

One thing I gleefully identify with is the level of restless frustration experienced by BBC’s Sherlock during boredom (not that Sherlock is necessarily ADHD - let’s not open that diagnostic nightmare of a discussion please!).

I would like to see more of a struggle with internal noise shown in media. Often I see the bouncy, silly outsider view of the disorder and I would greatly appreciate seeing a wider range of symptoms/experiences, including the ones that make us want to pull out our hair. For me, off medication, being in a room where I am required to be silent, still, and focusing is basically my own personal hell.

It doesn’t at all need to be all doom and gloom, just not squirrel-chasing-8-year-old-boy-stereotype so much please!

First of all, philosophium, thanks for asking!

I’m glad ADHD community replied, because they’re a good source of facts about ADHD presented from an ADHD perspective. So, you learn some of what you’d get in a psych textbook, but also what it feels like from the inside.

If you’re really starting from zero, this Buzzfeed article is a nice place to start.

Here’s some miscellaneous information about ADHD that will hopefully help you write more accurate, and less stereotypical, characters.

1) We’re Not All Extraverted, Hyper, Happy Go Lucky Males. We can be male or female, child or adult. I’d love to see an introverted, non-hyperactive ADHD character, ideally a male one. Or an ADHD character who obsessively overthinks, and is prone to anxiety and perfectionism.

2) Look at Both Extremes. In real life, some people with ADHD can only multitask while others can only hyperfocus. Some people with ADHD can focus on the details while ignoring the big picture, others see the big picture brilliantly but miss all the details, while others can bounce back and forth but can’t see both at the same time. Some of us are laid back and prefer to go with the flow, while others react to their disabilities by becoming extremely perfectionistic and trying to plan everything ahead of time (me). Some of us have IQ in the gifted range (see “need for stimulation”), while others have low IQ or severe developmental delays (children who are born prematurely, have lead poisoning, or who have fetal alcohol syndrome often have ADHD). Almost all the people I know with ADHD are artists, scientists, or both.

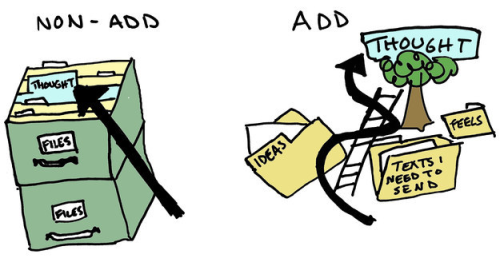

3) ADHD Is a Disability of Executive Function. Executive function is a confusing mess of tasks performed by the frontal lobe that allow us to control our behavior and respond flexibly and optimally to a changing environment. Some executive functions include working memory, inhibition (i.e., stopping oneself from doing or thinking something), task switching, sustained attention, planning, decision making, prioritizing, prospective memory.

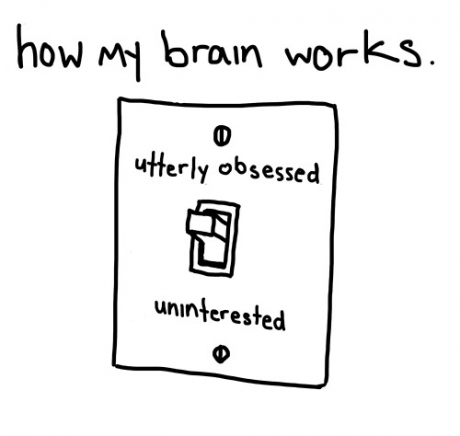

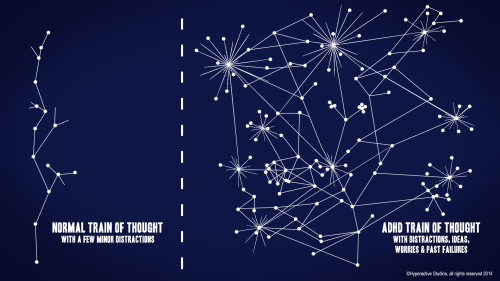

4) We Can Pay Attention, We Just Can’t Regulate It. We can focus for hours on something that interests us, or on procrastinating. We’re not good at focusing on things that we find boring or that don’t matter to us. We also aren’t good at controlling the amount of attention we pay. This is how our attention works:

5) ADHD is a Production Problem, Not a Learning Problem. A lot of us excel at getting information into our brains, especially when it interests us. The difficulty is producing something that shows what we’ve learned by a deadline–be it a paper, a presentation, or a project. For some of us, the hardest part of any assignment is finishing it and turning it in on time in the correct format. If we can do these things, we’ll probably get an A; if we can’t, we’ll probably fail. As a result, the idea of “gradating your effort” doesn’t apply well to us (telling us to “stop being so perfectionistic and do the minimum” makes no sense to us), and our achievement can be all-or-nothing.

6) We Don’t All Get Bad Grades, Or Misbehave in School. Those of us who are smart, learn easily, and are interested in school can get good grades until the demands for organized, well-formatted, and on-time work overwhelm our abilities to produce (see #5). Those with inattentive ADHD, when bored, tend to daydream, look out the window, or draw rather than misbehave. Teachers might not notice these students at all–or might even see them as well-behaved and a joy to teach.

7) Need for Stimulation. As ADHD community said, an ADHD character who is wildly intelligent, and when bored, feels as if they’re in a sensory deprivation tank. Boredom is Chinese water torture. Each second is a drop of water. How we react to this varies. Some are constantly bored and highly aware of their search for stimulation. Others, like me, think they’re never bored because they’ve become very good at keeping themselves occupied. I always carried a book to read and a sketchbook to draw in with me, and I would read even while crossing the street. Only when I needed to learn to cook did I realize I can get bored within literally 10 seconds.

8) Sometimes, what’s “hard” or “complex” is easy for us, and what’s “easy” or “simple” for others is hard for us. Especially if we’re also gifted. See: http://neurodiversitysci.tumblr.com/post/12568168808/the-complex-is-simple-the-simple-complexif

9) Memory Problems. I’d like to see an ADHD character who has a terrible memory, and struggles with the psychological/identity consequences of that and not just the academic ones. They’re constantly writing things down, and constantly worrying about how to organize the record of their life, or about what would happen if it were destroyed in a fire/flood/other accident. The most impaired form of memory, though, is prospective memory, the ability to remember what you are going to do. Memory problems are some of my worst ADHD traits, yet I rarely see them discussed.

10) Paradoxes of Reminders and Clutters. Because of our memory problems, you might think the answer is simple: just put post-it notes everywhere. And indeed, even other ADHD-ers often advise us to use colorful post-it notes and put them everywhere. However, visual clutter shuts our brains off, so we stop looking at these post it notes and reminders–or even look right at them and don’t register their existence. Another version: if items aren’t visible, I forget that they exist. (For example, I forget about food in the back of the refrigerator until it goes bad; I forget about clothes in the corner of the closet). But if too many things are visible, I stop being able to see them. They just look like clutter, an undifferentiated “bunch of stuff” to me. It would seem like the answer is to get rid of as much stuff as possible, but the decisions involved take hours and leave me exhausted.

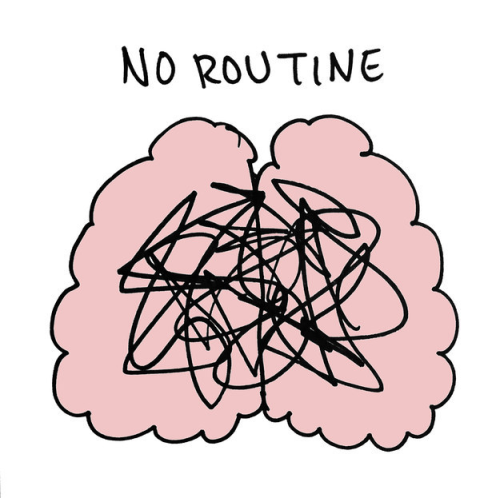

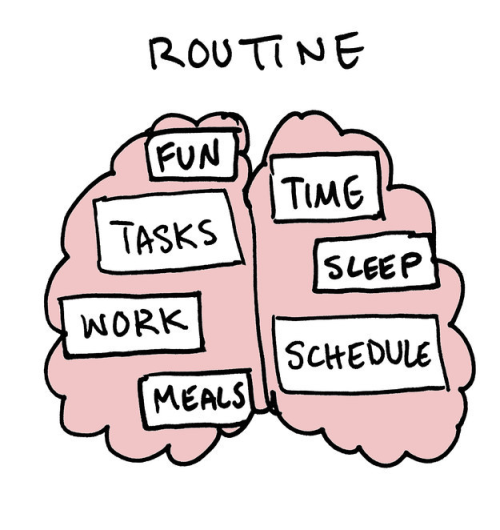

11) The Paradox of Routines/Habits: Habits help us function despite our inability to remember what we’re supposed to be doing and our tendency to get sidetracked in the middle. That’s because habits require no thought, attention, or memory–we do them automatically.

The problem is, it’s almost impossible for us to make the habit in the first place because we can’t consistently remember to do it. So, you get people with ADHD who forget to take their medication for the very reasons they need it in the first place.

12) Inconsistency. An ADHD character whose functioning is inconsistent from day to day and so feels he/she can’t rely on him/herself. There’s a lot of research on this “intra-individual variability” and indeed, it ranks among the most consistently-found traits found in both children and adults.

13) When we’re exhausted or overwhelmed, or a life crisis happens, we can stop being able to do basic things we used to be able to do. Maybe we used to be able to get to work/school on time, remember when assignments were due, or have a consistent morning routine. Now we’re no longer able to get out of the house on time, remember our assignments, or remember to take our medicine or brush our teeth in the morning. When this happens to me, I realize how much energy and attention I’m putting into doing “basic” things and wonder when I’ll ever “get them under control” so I can focus on learning new things.

14) Slow or Inconsistent Processing Speed. We don’t always talk fast and display high energy (I wish!). Some of us struggle with fatigue and slow processing speed (see: Sluggish Cognitive Tempo, a proposed subtype of Inattentive ADHD). For example, I usually feel mentally and emotionally tired–I feel after a full night’s sleep the way most people do after three or four hours of sleep. The more tired I feel, the more difficulty I have concentrating, multitasking, remembering to do things, and making decisions. This is one reason why stimulants and even wakefulness medications can help. Some people, like me, have inconsistent processing speed. Sometimes I think and talk so fast it irritates others, I find what’s happening around us boring (think of the world’s longest meeting), and I interrupt others. Other times, I am just about to answer someone’s question when they irritably repeat themselves or ask why I’m taking so long to answer. It feels like I’m thinking and talking at the normal speed, but others’ reactions make clear that we’re going much faster or slower than they are. Our relative strengths and weaknesses can affect when we think faster vs. slower than normal. For example, I finished the verbal portion of the SAT and checked my answers multiple times halfway through the time limit. I then had to sit there, bored, until the time was up. On the other hand, I ran out of time on the math section before I could check my work.

15) Some of us are socially awkward penguins, not graceful adrenaline junkies. There’s a stereotype that we’re adrenaline junkies who perform surgeries and jump out of planes. Or, we’re social butterflies who compensate for our school difficulties by playing class clown or making friends with everyone. But some of us are physically or socially awkward. Socially, lapses in attention can make us say things that come off as awkward or rude. Our poor sense of timing and inconsistent processing speed can throw off our conversational rhythm, making us interrupt–or just appear odd. Many of us also have motor coordination delays and difficulties (and research bears this out). As kids, we might have had difficulty using scissors, writing, tying our shoes, throwing or catching a ball, or riding a bike. We can have social and/or motor difficulties without meeting criteria for autism spectrum disorder. (Although a lot of people with ADHD have autism, too–see below).

16) Anxiety. Most of us develop anxiety, for all sorts of reasons. We’re prone to overthinking, to begin with. We have to worry about others misunderstanding us and calling us lazy, stupid, flaky, or rude. Some of us develop an exhausting habit of “constant vigilance” because we know of no other way to avoid making ADHD mistakes (losing things, forgetting things, math/writing errors, running late, etc.).

17) Co-occurring conditions. ADHD rarely rides alone. People with ADHD often have dyslexia, math disability, sensory processing disorder, dyspraxia, autism spectrum disorder, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or allergies. Immune system or digestive problems might make us even more inconsistent.

18) Our family members are likely to have ADHD or autism–diagnosed or otherwise. Many people report being diagnosed with ADHD after their own children were diagnosed. Like autism, dyslexia, and other disabilities, ADHD is highly heritable, meaning that it’s highly likely that someone with ADHD traits will have children with the same traits (and their parents probably have them, too). I have a younger brother on the spectrum, and have met a number of other older ADHD sisters with younger autistic brothers. While the gender thing may be a fluke, I have read that ADHD and autism share genetic causes and can run together in families.

19) We have a variety of attitudes towards our ADHD. Some of us see ADHD as uniformly disabling, preventing us from using our talents and passions Other people see ADHD as a gift. People with each of these viewpoints sometimes see the opposite as harmful to people with ADHD. Still others view ADHD as a trait like any other, which can have positive or negative effects depending on how one chooses to use it and what environment one is in. (Personally, I see ADHD, in general, as a set of traits. However, I see mine as mostly negative because they have been impairing me recently and preventing me from pursuing a longstanding dream. I view my ADHD traits as preventing me from using many of my talents and passions. However, there are environments where they’d be less disabling, and I’m currently trying to find them).

20) Being diagnosed and labeled can have good effects, too. There’s a sense of relief, of understanding, of not being broken, of having words for one’s experience. The book title “You mean I’m not lazy, stupid, or crazy?” captures the feeling pretty well, I think. I’ve also written about the benefits of diagnosis and the crappiness of growing up without diagnosis a LOT–see this, this, most of all, this:

“…that sense that there was some mysterious thing wrong with me. (Do you know what it feels like, to carry around a sense that something is wrong with you, always ready to erupt, and not know what’s wrong or why? To have people constantly pointing out when you do something wrong but never acknowledging that mysterious brokenness–pointing out the elephant dung and squished sofa in your living room but never mentioning the elephant or offering to help get it out of your living room? And since no one will talk about the elephant, you have no idea how to get it out of your living room, so you’re just stuck with it there. No one can tell you how to fix what’s broken).”

21) Stimulants don’t necessarily turn you into a zombie. They aren’t necessarily a cure-all, either, and some of us choose not to take them. I have yet to find a medication at a dose I can take daily, because it makes me completely lose my appetite. I only take it during emergencies–high-stakes days where I’m not able to function, and/or due to other health problems acting up, I can’t drink coffee. This isn’t the only side effect. Some people get migraines from stimulants. These medications can also slightly stunt children’s growth.

22) ADHD can be seriously disabling. ADHD looks on the surface like something “everyone deals with,” but as the experiences I’ve described above suggest, it can cause serious problems in school, work, and relationships. The large-scale MTA study, which followed hundreds of girls and boys with ADHD into adulthood, found some poor outcomes, including higher rates of self-injury and mental illness; adolescent substance use; eating disorders; and poorer relationships with peers in adolescence and parents and partners in adulthood. ADHD has also been linked to lower test performance, poorer education and work performance, greater risk of accidents, and obesity. Researchers and the media tend to describe these problems as a result of the ADHD traits themselves, especially impulsivity. But the way we treat people with ADHD probably has a lot to do with the bad outcomes. One contributing factor: many, especially those diagnosed late in life, develop crippling shame and self-hatred.

23) We’re also awesome! People with ADHD can be creative, energetic, passionate, thoughtful, academically skilled, empathetic, entrepreneurial, and more. Famous people in every walk of life have diagnosed ADHD, and many past geniuses have traits. Like other disabilities, ADHD colors how we experience and act in the world, but it does not diminish us or make us less human.

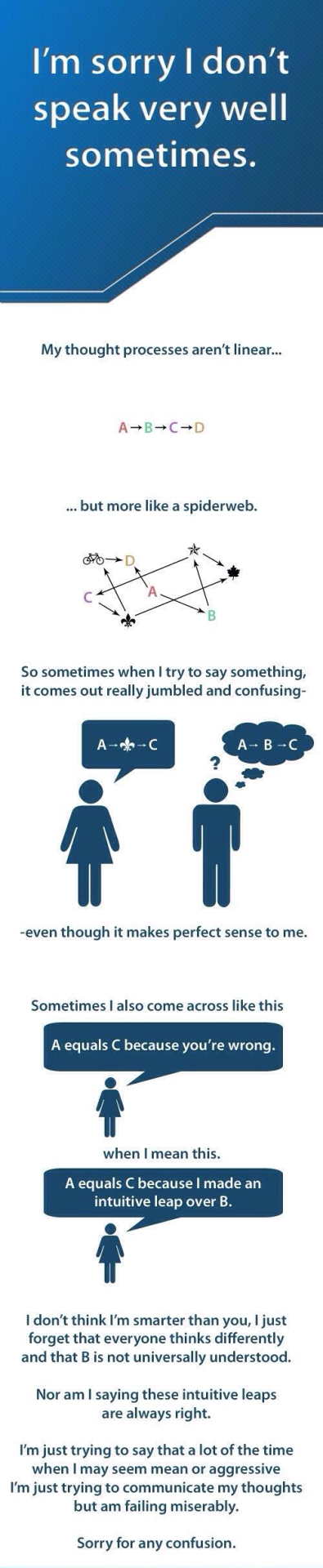

24) Bonus point that doesn’t fit anywhere: I’ve noticed that smart women with ADHD have a very distinctive style of talking. We talk fast, crowding as many ideas into a sentence as possible before we forget what we’re saying. We are trying to pack a lot complicated thoughts into a short amount of time. We veer off on tangents whenever someone says something interesting. If two of us start talking, we can go on for hours and never run out of things to say–and also never return to the topic we started with. To those who do not have ADHD, we sound rambling or incoherent. To other women with ADHD, we make perfect sense and the conversation feels exhilarating, with the energy building increasingly as we talk. We sound incoherent to others but not each other because our thoughts are arranged in a very dense and logical web, but we move through the web in a zig-zagging pattern based on associations instead of a straight line. The zig-zag pattern happens in part because with our short working memory, our span of awareness is extremely short. So we operate on associations; everything reminds us of something else. Other people’s words, objects in the room, and music we hear reminds us of something, but then then we forget what we were talking about before. We’re constantly forgetting what we were talking about or what we were doing in the middle. As a result, some of us have a bad habit of interrupting others in order to get our message out before we forget it.

If you have any more questions, feel free to ask! Sorry this was so long…

https://neurodiversitysci.tumblr.com/post/139769513631/adhd-community-philosophium-do-i-have-any