Trains in Anime (and other random opinions) — Hawkeye and language

https://trainsinanime.tumblr.com/post/130192891553/hawkeye-and-language

No, not an Age of Ultron joke. There are millions of different definitions of language. For the purposes of this discussion, I’ll just use a simple but incredibly broad one, partly because I’m lazy but also because it’s necessary here: A language is any structured system to convey information using symbols. Those symbols can be spoken sounds, letters, but also a lot of different things.

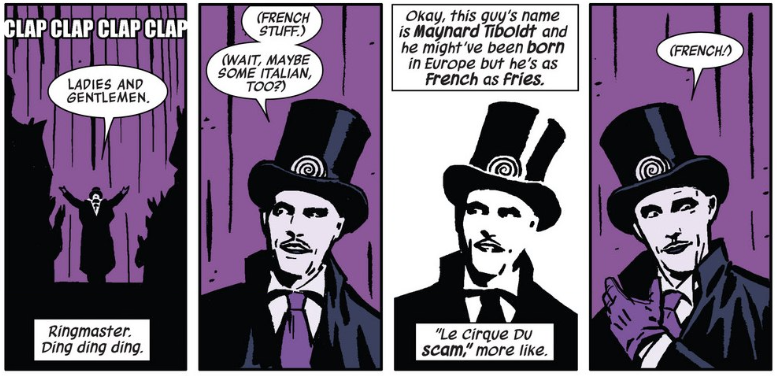

Hawkeye’s use of language is very interesting. Obviously the basic level here is the standard English language, but right away we see it playing with its conventions, for example in the obvious cases of internal editing.

There is always a disconnect between “actual events” and their comic version, something many comic artists and writers try to hide with realistic dialogue and graphics. This, on the other hand, explicitly draws attention to its artificial nature. It works because this is an explicit representation of Clint Barton’s point of view and mindset: This is literally what he understands. It is an expansion of the language, conveying information that normal dialogue couldn’t.

Playing with language in comics, even expanding a bit beyond realistic depiction of dialogue, is nothing new or unique, though I do always like it when it happens, e.g. this adorable bit in a preview one-shot for Gotham Academy:

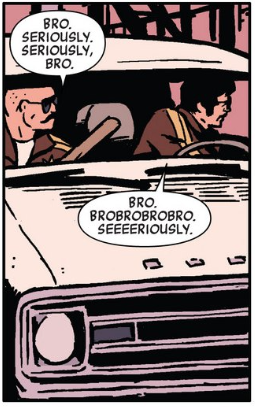

A very distinctive example in Hawkguy is the use of “Bro” and “seriously”, which can be all a good dialogue needs at times.

The comic makes it obvious that the actual dialogue, and what we understand of it, are two separate things. This is a comic that likes to have fun on the written language level. But it goes beyond that.

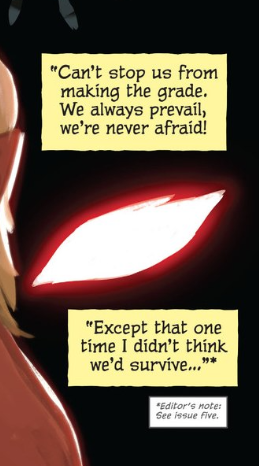

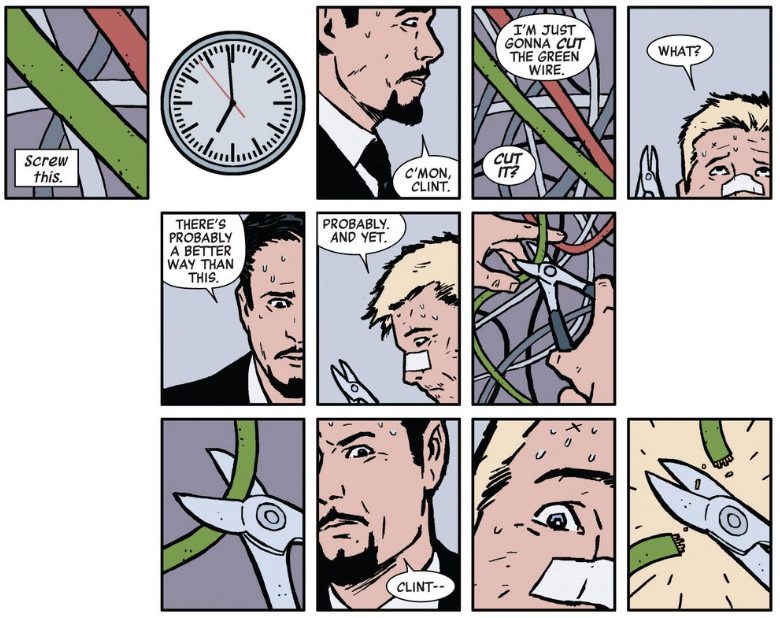

The structure of comics is a form of language in itself, at least using the very expansive definition, and you can likewise see Hawkeye play with it to convey its information, for example by subverting our expectations…

There are many more examples. The comic loves its time jumps. One of the best parts ever is when five successive issues show the same evening, and part of its introduction and its follow-up, each from a different perspective, to understand what each character thinks, but also how they all have incomplete information.

So far, so good. Hawkeye is a very ambitious and complex comic that pushes what comic language can do, and generally succeeds. I do think it got the whole non-linear stuff better over time; in the first issue it was harder to follow the structure than later, even though it didn’t get easier.

And then it goes ahead and invents a completely new language, for one single issue.

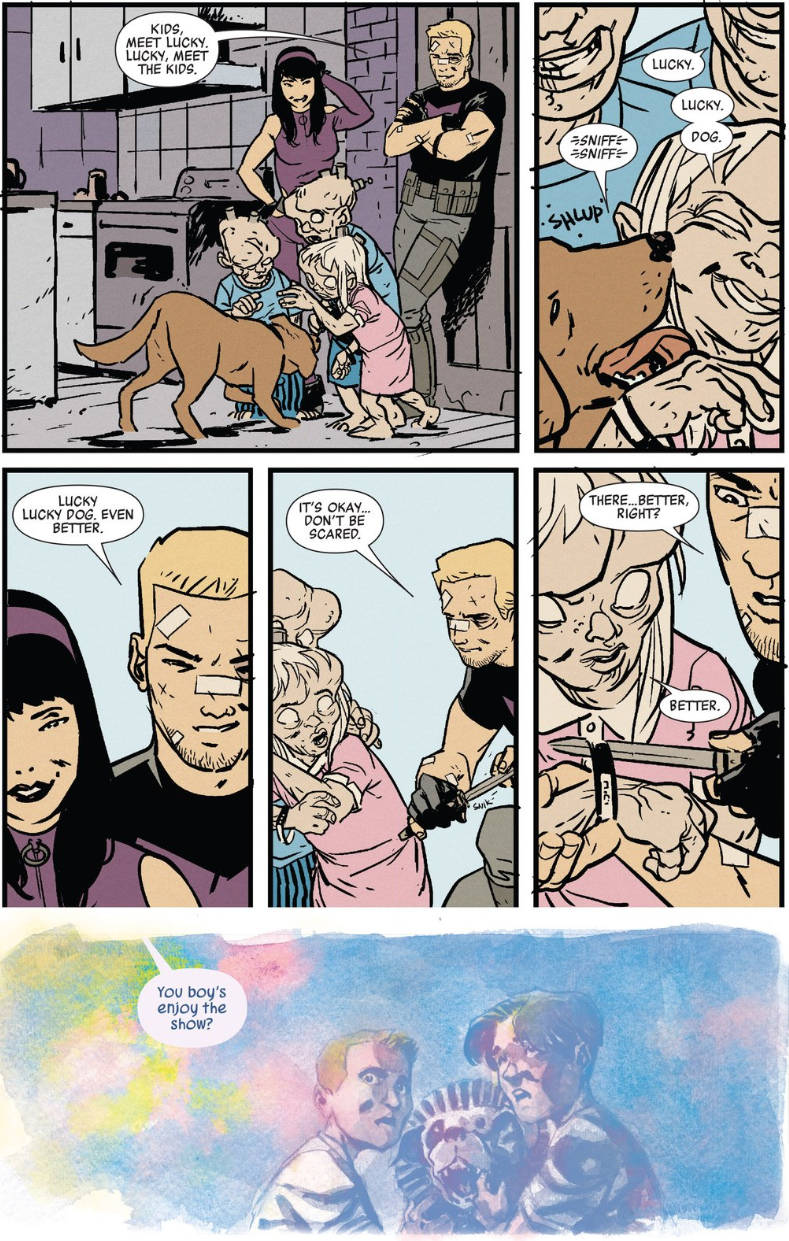

Here is where the expansive definition of language really becomes necessary. Issue 11, generally known as “The Dog Issue”, shows a new symbolic system that isn’t spoken, nor written, but it is a structured and effective way of telling a story. It is an interesting language, too, with the way it portrays structure mostly in form of clusters instead of linearly.

And it also talks about human language. Lucky is not a magical wonder-dog. He can’t read or speak, and he cannot really understand human language. But he does understand that it is a language, and he can understand parts of it. Which is portrayed in the comic by again, playing with language; here by only showing the words that Lucky can, in some form, distinguish. The amount differs heavily depending on the conversation, but it’s clear that he mostly gets stuff that people use to talk to him or around him. He can understand his name, various commands, but he also understands the names of the various humans in his world and various of their usual expressions. This provides a commentary on these people as well. Apparently someone taught him to understand the word “ass”, for example.

This is one of the most inventive uses of comics and their possibilities I’ve ever seen. And it works, which is by no means a given for something as complex as this. To get there, it is based on graphical symbols we can understand, but arranged in new ways to convey new information. And as the story progresses, it gradually cranks up the complexity to really spread out the dog world.

And then they went ahead and did it again.

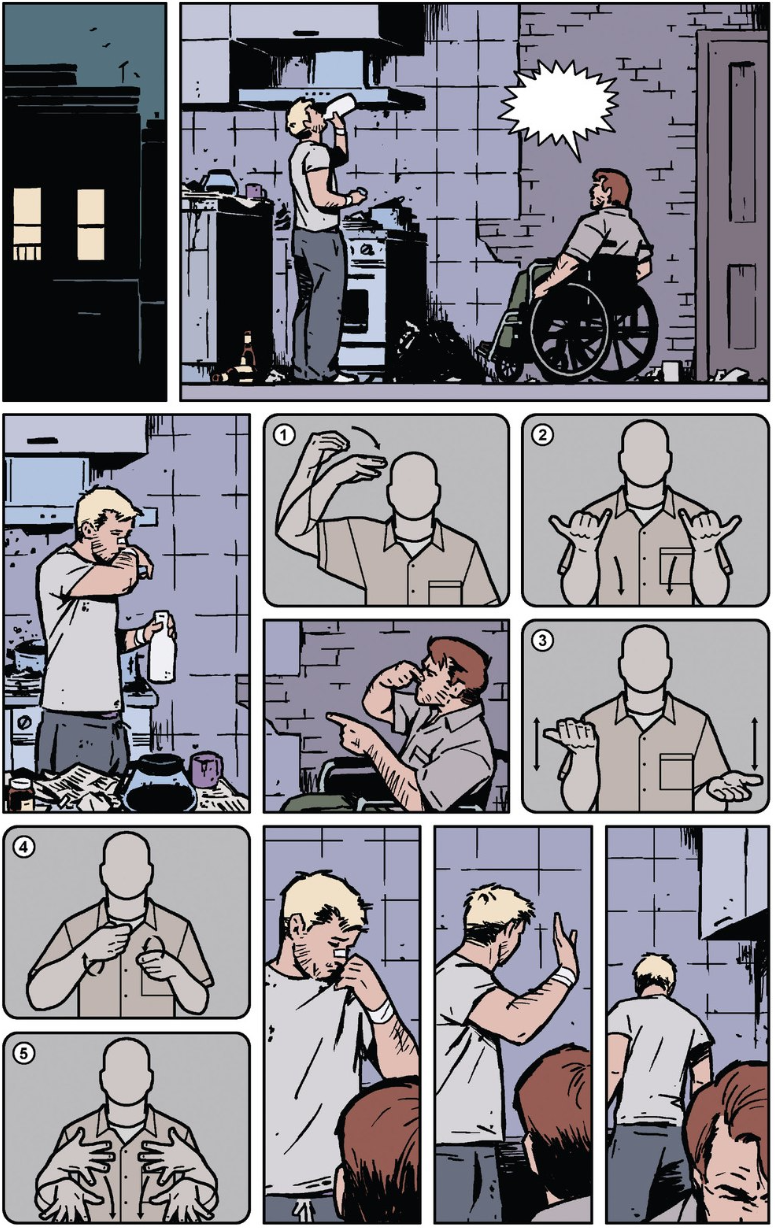

I’ve heard some people say that this issue is written in American Sign Language. That isn’t exactly wrong, but it doesn’t tell the whole story, because the way of representing it is new. Instead of having people use it in panel, ASL here is used outside, once more using graphical symbols.

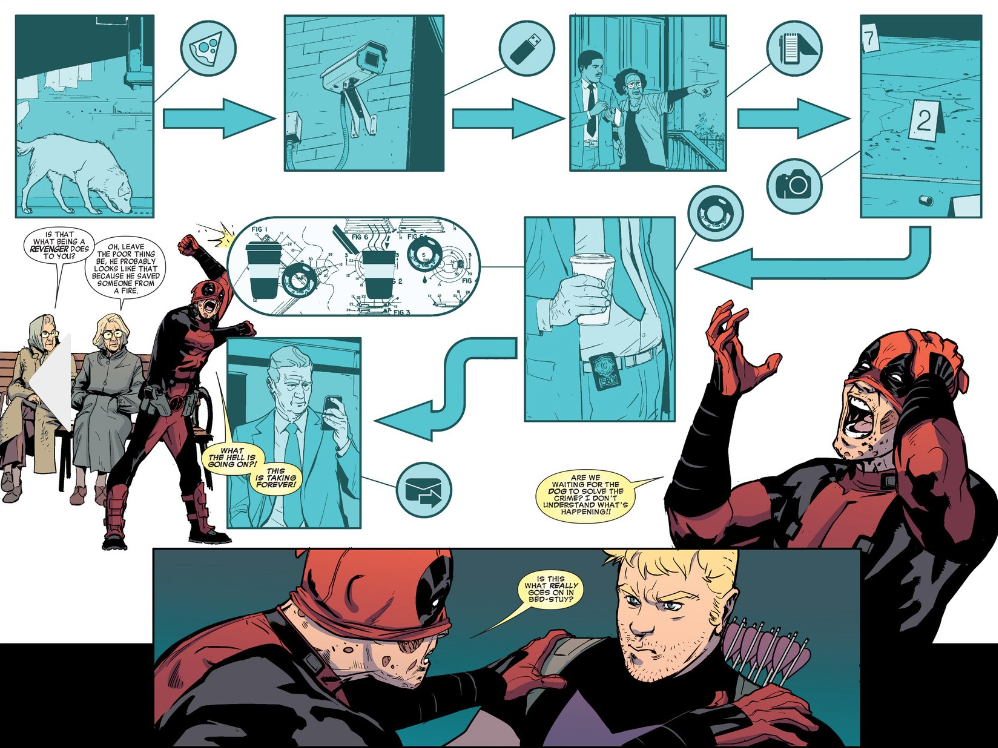

Compare this to Batgirl (2011-) #37, where the titular hero is analyzing pictures of an impostor of hers for clues:

It’s also ASL (I’m assuming; I didn’t actually check), but in a very different role. Here it is used to hide that communication is taking place, both from the reader and from other characters. Barbara Gordon is awesome because she can figure it out anyway. (Also these aren’t holograms, it’s a representation of her photographic memory; that comics’ own visual language.)

In Hawkguy, the communication is explicit and in your face. When you think about it, these are some of the biggest words ever used in comics.

Unlike the dog issue, these are symbols that most readers will not readily understand, and that is a huge part of the point. Language is exclusionary if you don’t know it. It was that case in issue 11, but it is much more important (and a big part of the story) here.

A minor example is shown in the same issue at the airport:

None of the people in this gang speak English well, but they speak it better than any of each other’s languages. It is something that connects them, but also highlights their differences. Two of them can’t figure out the “arrivals” sign, assuming it means “alligators”. It is meant to be universal, and that works to some degree, but it is also another form of sign language with its own barriers.

The comic also features lip reading, and again, shows a different use of language.

It is English, but filtered, distorted and unclear, and the comic takes great pains to show this. The structure of language here is unreliable, impeding communication, but in some contexts, it’s also the only way communication can take place at all.

(Also, I love how the font used for Clint shows his uncertainty with spoken language now that he can’t hear himself. It’s very subtle but effective.)

All these things are based on standard comics language, partly on standard english or standard recognized signs, but then they use it as a starting point to create something new. A side-effect of that is that it really has to be a comic. For many of my favorite other titles, I could easily imagine a movie or animated TV show or book or video game adaptation. Not here.

Hawkeye has found many fans and imitators amongst Marvel comics makers

(Secret Avengers #1, Hawkeye vs. Deadpool #0, All-New Hawkeye #3)

And probably beyond; if you know any examples, I’d be glad to hear about them! But all of them just copy the style without copying the creativity that made it awesome. Hawkeye is true art, in a way many other comics are not.